|

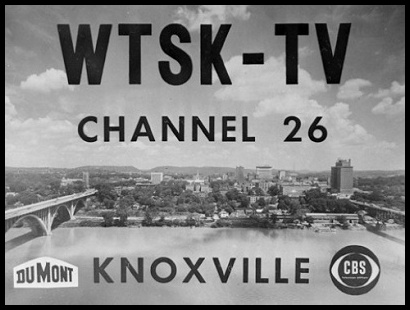

Channel  : UHF : UHF

"If there had been four VHF outlets in the top

markets, there's no question DuMont would

have lived and would have eventually turned

the corner in terms of profitability. I have no

doubt in my mind of that at all."

The FCC's Dr. Hyman Goldin, in an interview

with Gary Hess in 1960 (see Channel 11).

One of the factors hampering DuMont in the development of

its television network was the "freeze" on new TV stations imposed by

the FCC in 1948, and the subsequent decision to allocate UHF channels to

television. In assigning television channels to various cities, the FCC

found that it had located a number of stations too close to each other

(channel 4 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, for example, was too close to

other stations on channel 4 in New York City and Washington, D.C.,

resulting in interference.) At the same time, it was becoming evident

that the existing spectrum of twelve VHF channels, 2 through 13, was

inadequate for nationwide television service. The FCC, therefore,

decided to call a halt to approving new TV stations while it

investigated these problems. DuMont's WDTV, granted a construction

permit in 1948, was one of the last television stations to be authorized

before the "freeze" took effect.

What was intended as a six-month moratorium on the

authorization of new television stations dragged on for years, as the

allocation of UHF channels and the possibilities of color television

were debated. DuMont, believing that UHF would not be competitive for

years, and hoping to establish more VHF network affiliates in large

cities, submitted to the FCC in 1949 a document titled A National

Television Allocation Plan, which proposed that the top 100 markets each

be allocated four VHF channels (one each for CBS, NBC, ABC, and

DuMont), and that additional UHF channels then be assigned to the

largest cities as needed, as well as to smaller markets. This would have

placed DuMont on an equal footing with the other three networks in most

cities, but it also would have greatly displaced existing stations, and

the plan was never adopted. (One can certainly understand why VHF

broadcasters in cities like New York and Los Angeles would have lobbied

hard to avoid moving to the UHF band.)

The "freeze" was finally lifted with the issuance of the

FCC's Sixth Report and Order in 1952, by which time 108 VHF TV stations

-- most of them well-established and profitable network affiliates --

were on the air in the United States. The Sixth Report and Order

required some existing TV stations to change channels (WDTV was one of

these, and switched from channel 3 to channel 2 on November 23, 1952),

but only a few existing VHF stations were required to move to UHF, as a

handful of VHF channels were deleted in places like Peoria, Fresno, and

Bakersfield to create markets which were UHF "islands." The report also

set aside a number of channels for educational television, which

hindered ABC and DuMont's quest for affiliates in markets where VHF

channels were reserved for non-commercial use.

Most significantly, however, the Sixth Report and Order

provided for the "intermixture" of VHF and UHF channels in most markets,

which in the 1950's was an unmitigated disaster. UHF transmitters were

not yet powerful enough, nor receivers sensitive enough (if they

included UHF tuners at all), to make UHF viable against entrenched VHF

stations. In markets like Youngstown, Ohio, Scranton/Wilkes-Barre,

Pennsylvania, and Fort Wayne, Indiana, where there were no VHF stations

and UHF was the only TV service available, UHF survived. In other

markets, which were too small to financially support a television

station, too close to VHF outlets in nearby cities, or where UHF was

forced to compete with more than one well-established VHF station, UHF

had little chance for success.

While it is almost unheard-of for a television station to

go dark today, in the 1950's the demise of UHF TV stations was

commonplace. In Broadcasting The Local News, Lynn Boyd Hinds

tells the story of WENS, channel 16, a UHF station in Pittsburgh which

tried to compete with DuMont's WDTV. Dan Mallinger, a former WENS

employee and later the head of Pittsburgh's AFTRA chapter, explained to

Hinds why so many UHF TV stations signed off in those early years:

There weren't any viewers. At that time, no TV set

had a UHF band on it. You used to have to get a little

box, a converter. And you hooked the converter into

the TV set and then you had to tune it, fine-tune it.

And you never got a fine-tuned picture. It was always

fuzzy. And nobody bothered to buy them. So I

remember at one point the station bought a couple of

hundred of them and went around and gave them

away to all the ad agencies. At least the agencies they

were trying to sell could see it. And everybody at the

station got one to take home. But there was no

viewership, none whatsoever.

1953 Philco UHF converter

(author's collection)

Realizing that under the terms of the Sixth Report and

Order, its future depended on the success of UHF, DuMont bought a UHF

station in Kansas City and attempted to make it viable. The tale of

DuMont's venture into UHF ownership is brief, but enlightening. Television Digest announced the acquisition in its issue of January 2, 1954:

DuMont became the first network to go into UHF

when it acquired Kansas City's KCTY (Channel 25)

from UHF pioneer Herbert Mayer's Empire Coil

Company at 12:01 a.m. New Year's Day. DuMont

already owns three VHF (stations).

The transaction came suddenly, was first broached on

December 29, and approved by the FCC at a special

meeting on December 31. DuMont took over all

equipment and a full 5-year lease on the real estate, as

well as station's obligations, for a nominal cash payment

of $1. The station is well-equipped, even to a remote

unit, has specialized in local originations, (and has)

cost its owners some $750,000 to date in equipment,

property, and operating losses.

DuMont immediately dispatched Donald McGannon,

its assistant director of broadcasting, to supervise the

changeover, and announced that the acquisition will

put the "DuMont network, research and manufacturing

divisions in a position to study at firsthand the problems,

both financial and commercial, faced by (UHF) station

owners." KCTY's staff will be retained intact, at least

for the time being.

The network will funnel 21 of its shows to the station

weekly, and plans to begin a large-scale campaign to

add to the claimed 60 to 70 thousand UHF-equipped

sets in the area. It's also understood the station will

get the first 15 kw DuMont UHF transmitter, when

available (it now has an RCA 1 kw transmitter).

In the same issue, Television Digest also reported some of the problems faced by KCTY's previous owner:

Kansas City was (Empire's) second UHF venture,

its first under the gun of VHF competition. When

KCTY went on the air last June, the only other station

there was pre-freeze WDAF-TV, and other VHF

applicants appeared to be headed for endless FCC

hearings. But mergers and dropouts quickly resulted in

three more VHF rivals...who were able to grab

off most of the local business due to VHF's greater

coverage in heavily VHF-saturated Kansas City.

Vast efforts and funds were poured into the UHF

station in an attempt to gain a foothold, but within a

month, it was evident that the public wasn't willing to

convert fast enough when it could get the programs of

three networks on VHF (KCTY had DuMont).

KCTY went on the market, first at $750,000, then

$400,000, finally $300,000. There were no takers at

any price -- nobody even willing to name his own

figures.

(Empire Coil owner Herbert) Mayer considered going

off the air and salvaging what he could from the sale of

his equipment and property -- which would have been

a better deal financially than the DuMont transaction --

but decided such a move would have a depressing

effect on UHF.

DuMont's ownership of KCTY, however, did not last very long. On February 13, 1954, Television Digest reported:

DuMont this week decided to abandon its UHF

experiment in Kansas City in the interest of "sound

business judgment." The sudden announcement at

week's end told of (DuMont's) decision to close down

KCTY (Channel 25), which it acquired just six weeks

ago from Empire Coil Company for $1 ...

The network said it had studied the situation carefully

and concluded Kansas City viewers were adequately

served by their three VHF outlets. The statement by

Dr. Allen B. DuMont stressed that the problems were

"peculiar to Kansas City and not necessarily fundamental

limitations of UHF broadcasting in general."

KCTY will turn off (the power) February 28th to

become the third UHF station to go off the air --

out of a total of 130 UHF starters. The other two

were Roanoke's WROV-TV and Buffalo's WBES-TV.

Former DuMont managing director Ted Bergmann summed up the company's experience with KCTY in Jeff Kisseloff's The Box:

It had no audience...It cost us a quarter of a million

(dollars) to shut it down. It proved that UHF could

not compete with VHF.

There would be many more UHF failures in the next few

years to prove Bergmann right -- and DuMont would be involved with many

of them. In 1953, DuMont touted WGLV-TV, channel 57,

in Easton, Pennsylvania (a suburb of Allentown) as a high-power UHF

installation which was "100% DuMont equipped." This was, asserted

DuMont, the future of UHF television. Nevertheless, WGLV faltered when

the three Philadelphia VHF stations were permitted to build new, tall

transmitting facilities at Roxborough, providing primary coverage of

Allentown. WGLV and two other UHF stations in the market, as well as UHF

stations in adjacent markets like Atlantic City and Reading, Pennsylvania, quickly folded.

The UHF crisis soon drew the attention of Washington,

where, in 1954, the U.S. Senate held hearings on UHF, and where DuMont

made a last stand for the future of its faltering TV network. (DuMont's

testimony at these hearings is available in its entirety as an appendix

in Ted Bergmann's book.) In the end, however, the hearings accomplished

very little. By 1960, according to Lynn Boyd Hines, there were only 75

UHF stations still on the air -- out of more than double that number

which had originally signed on -- and countless UHF channels left vacant

due to applicants dropping out, or construction permits which were

never built. It would take the FCC's "all-channel" legislation of 1964,

which required all newly-manufactured TV sets to be able to tune UHF

channels, to finally begin to make UHF profitable and successful. This

action came too late to save the DuMont network.

Ironically, in the early 1960's, the FCC made a few

changes to the VHF channel allocations table in order to accommodate

ABC, which was still suffering from a lack of VHF affiliates in several

key markets, but DuMont's fate had been sealed years earlier. As 1955

approached, the end was in sight.

For a listing of long-dark UHF stations, many of which were DuMont network affiliates, see Appendices Ten and Eleven.

(With regard to this particular page, the author wishes

to acknowledge his indebtedness to several articles which appeared in

consecutive issues of the Community Antenna Television Journal (CATJ) in

1974 or 1975. Although uncredited, these articles were almost certainly

the work of CATJ editor-in-chief Robert B. Cooper, Jr. The author

committed much of this material to memory at the time and has

paraphrased some of Cooper's work on this page. Also, the above excerpts

from Television Digest have been revised and edited for punctuation, capitalization, and clarity.)

Go to Channel 7: Finale

|

|