Channel  : Finale : Finale

"We didn't have a lot of stations, but we had a lot

more than ABC did...The only reason ABC survived

was they had been in the radio business, and they

got the Paramount backing."

Art Elliot, a former DuMont network salesman,

in Jeff Kisseloff's The Box (see Channel 11).

By 1954, DuMont was in a rather unenviable position. The

FCC's Sixth Report and Order had restricted the number of VHF stations

to two or three in most cities, preventing DuMont (and to a certain

extent, ABC) from competing on an equal basis with the other networks,

and requiring DuMont to utilize UHF stations for program clearances.

Unfortunately, these UHF outlets went unwatched, and

returned their licenses to the FCC in unprecedented numbers as they went

dark. On the other hand, CBS and NBC, which had prime VHF affiliates in

most markets, continued to grow their TV networks; and the stars of

popular DuMont shows, such as Jackie Gleason from Cavalcade of Stars and Ted Mack of the Original Amateur Hour, signed with the two major networks as their contracts with DuMont expired.

In addition to these problems, DuMont began to see its

primary profit source, television manufacturing, decline as a source of

revenue. Among over 100 manufacturers of television sets, DuMont was

highly ranked, providing a high-priced product to a luxury market in the

early years of television. Its slogan, "First with the Finest in

Television", reflected a commitment to quality. But as television grew,

conditions soon changed, as reported by Craig and Helen Fisher in the

book Metromedia and the DuMont Legacy, published by the Museum

of Broadcasting (now the Paley Center for Media) in conjunction

with its DuMont tribute in 1984:

DuMont television sets were the Cadillac of the

industry ... But GE, RCA and Westinghouse soon

established high-volume, low-profit operations

with which DuMont did not successfully compete.

Of the profitability of the DuMont network itself, R.D. Heldenfels writes:

Although DuMont took in money — $12.3 million in

advertising revenues in 1953 — that was one-eighth

of what CBS was getting from its TV operation.

And it took a crazy quilt of deals for DuMont to

make that much. Acting more like an advertising

agency than a national network, it sold sponsors

ad time on its shows in as few as a dozen markets

carrying the program, then sold time to other

sponsors in other markets, and so on.

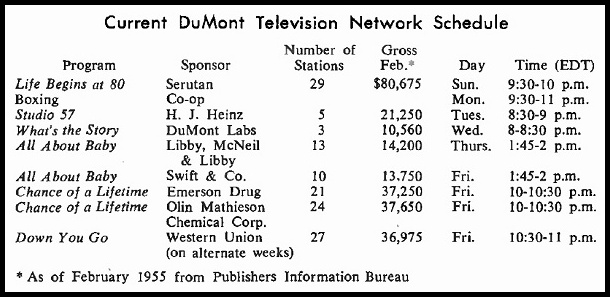

This strategy, probably born of necessity due to DuMont's

low number of "live" program clearances, can be seen repeatedly in

trade advertisements of the period, all of which suggested in one form

or another that the major networks were too expensive, and that DuMont

offered advertisers the opportunity to reach (presumably smaller) TV

audiences more economically. In his book, Ted Bergmann explains:

We had realized that our lack of a radio network and

all the connections with stations that would come with

it made it imperative that we create something to set us

apart from our bigger and more powerful competitors...

the "something" we decided upon was "cost efficiency".

We intended to create opportunities for advertisers

who were in a position to lay out fewer dollars. We

eliminated the "must buy" station lineup required by

the other networks, and turned one of our greatest

liabilities -- our difficulty in live station clearance --

into an asset by allowing advertisers to pick and

choose the network stations on which they wanted

their programs carried.

DuMont might have survived as the third national

television network, were it not for a sudden change of fortune at the

other struggling network, ABC.

As noted earlier, ABC and DuMont battled for affiliates,

and to clear shows on other network stations. ABC was late in

establishing TV stations of its own, and for its first few years was

fourth behind DuMont, which apparently had a legitimate opportunity to

establish itself as the third national network. In 1953, however, ABC

merged with UPT (United Paramount Theaters, not to be confused with

Paramount Pictures, which was a stockholder in DuMont), and the

resulting infusion of cash revitalized the network. DuMont was already

losing ground to CBS and NBC, and with ABC's resurgence, was doomed.

Realizing this, DuMont made a last-minute attempt to

merge with ABC. According to an account by Ted Bergmann in Jeff

Kisseloff's The Box, ABC executive Leonard Goldenson approached Dr. DuMont and Bergmann and said:

What do you think of merging our two networks.

Then we could successfully compete with NBC and CBS.

We'll take over all of your network commitments.

We'll pay you five million dollars, and we'll keep the

name of the network ABC-DuMont for at least five

years, which will give you the advertising for your

television sets.

At Dr. DuMont's direction, Bergmann worked out a deal

with ABC, but Paramount vetoed the plan. One wonders if the combined

ABC-DuMont network would have been a bigger player in television than

ABC by itself proved to be over the next decade, and if so, what this

might have meant for both DuMont and ABC; but the deal was never

consummated, and DuMont was headed for oblivion.

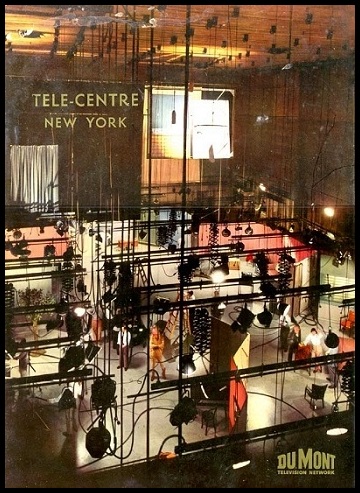

To make matters worse, DuMont had just spent five million

dollars to build its elaborate Tele-Centre in New York City, which

opened on June 14, 1954. The facility was a showplace, but was built at a

time when New York was fading as a network origination center and as

television was converting to filmed programs, rather than the "live"

shows which originated from the Tele-Centre. DuMont had put its eggs in

the wrong basket.

Falling behind as the other three networks became more

successful, and strapped for cash, DuMont sold its highly profitable

Pittsburgh TV station to Westinghouse in the fall of 1954 for $9.75

million, a record price at the time. This eliminated the leverage tool

which had enabled DuMont to obtain clearances for its programs in other

markets. While the sale provided ready cash for DuMont's operations, it

would prove to be a fatal blow to the network. Writes Ted Bergmann:

The sale of the station really spelled the end of the

DuMont Television Network, since the advantages

of owning the only outlet in the sixth largest market

in the country provided a major profit center to

offset the network's losses. We no longer had an

exclusive attraction to offer advertisers.

R.D. Heldenfels offers a glimpse into just how dire DuMont's circumstances were by this time:

The advertising situation worsened until the network's

revenues for the first six months of 1955 were less than

half of what they had been two years before and its

competitive position was awful. Broadcasting reported

that DuMont's six-month take was about one-seventh

of what a newly healthy ABC grossed in the same period,

about a fourth of what NBC averaged each month

and a fifth of what CBS did each month. DuMont's

stockholders demanded something be done in mid-1955.

It was only a matter of months before DuMont decided it

could not continue in the television network business. Based on the

conclusions in a report from management consultant firm Booz, Allen and

Hamilton delivered to DuMont on February 4, 1955, Ted Bergmann writes:

The decision...was then made to close down the

DuMont network and to continue operating the

New York and Washington stations as independents...

We began concentrating on Electronicam, hoping to

develop enough business to generate profits...and to

strive to become a "TV film network," offering

simultaneous exposure of a product on all stations,

as opposed to traditional syndication.

However, in early May of 1955, everything began to

come apart at the annual stockholders meeting of

the corporation.

In Watching TV, Harry Castleman and Walter J. Podrazik offer a less-than-benign version of the events leading to DuMont's demise:

In the face of such an all-around failure, Paramount

staged a coup d'etat in August, 1955, and at last took

complete control of DuMont. By teaming up with the

investment firm of Loeb & Rhodes (another major

DuMont stockholder), Paramount obtained a working

majority of stockholders and instituted immediate

changes. Dr. Allen DuMont was kicked upstairs to the

meaningless position of chairman of the board, and

Bernard Goodwin (a Paramount man) was installed

as president. Soon thereafter, DuMont announced that it

no longer considered itself a national television network.

This story is corroborated by Ted Bergmann's highly personal account in Jeff Kisseloff's The Box:

When all of this was going on, I remember sitting in

(Dr. DuMont's) study in his house, just the two of us.

It was all coming apart at that point. We were having

a drink before dinner, and he started to sob and said,

"I can't let them take my company away from me. I can't

let them do this." Then he recovered his composure,

but they did take it from him.

Slowly, DuMont began to dismantle its network operations.

On April 1, 1955, many of the entertainment programs on the network

(including Captain Video, DuMont's longest-running show) were

dropped. Bishop Fulton J. Sheen's last program aired a few weeks later,

on April 26 (he would soon move to ABC). By May, only eight shows

remained on the DuMont network, and the AT&T coaxial-cable

interconnection to DuMont affiliates in other cities was cancelled.

Inexpensive programs like It's Alec Templeton Time sustained what was left of the network during the summer months. A panel show called What's the Story?

was the last regularly scheduled non-sports program on DuMont, with its

final airing on September 23, 1955. After that date, DuMont reserved

its "live" network feed for occasional sporting events. The last program

of any kind on the DuMont Television Network was Boxing from St. Nicholas Arena with Chris Schenkel on August 6, 1956, although this show continued locally on WABD in New York City.

The death of the DuMont network, and the concurrent rise

of ABC, would establish the pattern of network television in the United

States for the next thirty years. (DuMont's demise is also credited for a

68% rise in advertising revenues at ABC in 1955.)

DuMont ultimately spun off its television stations into a

separate company called the DuMont Broadcasting Corporation. To

distance itself from what some saw as the failure associated with the

DuMont network, the name of the new company was eventually changed to

Metropolitan Broadcasting. In 1958, an investor named John Kluge

purchased Paramount's shares in the company, and WABD's call letters

were changed to WNEW-TV. (WTTG remains unchanged to this day.) In 1960,

the company became Metromedia.

The other DuMont assets were eventually sold or merged

with other companies. DuMont sold its television manufacturing business

to Emerson in 1958, and in 1960 DuMont Laboratories merged with

Fairchild Camera and Instrument, where Dr. Allen B. DuMont served as

group general manager and senior technical consultant until his death in

1965. While TV sets and other products bearing the DuMont name

continued to be manufactured by Emerson and Fairchild into the 1970's,

it was a pale reflection of DuMont's former glory. Eventually, the proud

DuMont name was retired.

All that remains of DuMont today are the fading childhood

memories of watching DuMont shows on DuMont TV sets; a sadly declining

number of network pioneers and employees who are still alive; some

advertisements and articles in print media of the time; and a handful of

kinescopes -- dim and blurry, but highly cherished today -- of the

"live" programs from a very innovative fourth network.

Allen B. DuMont was laid to rest in Mount Hebron Cemetery

in Montclair, New Jersey. While most of us will never have the

opportunity to pay our respects to Dr. DuMont in person, if you wish to

visit the site of his memorial through the auspices of the Internet,

please click here.

Go to Channel 8: Legacy

|